Some of us are left bored, confused or frustrated by group dialogue.

Others seek dialogue as spiritual enlightenment or as a fulfilling haven for psychological stimulation.

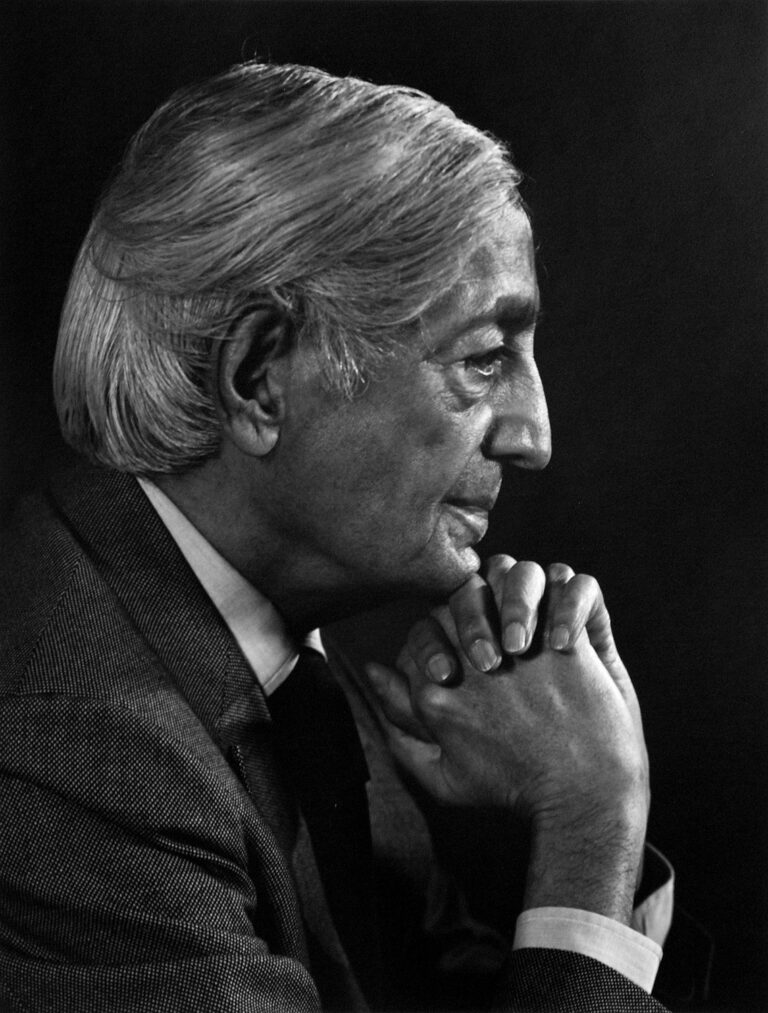

Krishnamurti and Bohm seemed to regard dialogue as significant in the whole field of self-knowledge. So what might be the culture of dialogue today and is it still meaningful?

What does group dialogue look like since Krishnamurti’s death? How has dialogue developed? Is there a form of “dialogue culture” showing up and if so, what is the nature of that culture? Is dialogue an environment that can foster real inquiry and leads to fundamental change; or does group dialogue incubate and even possibly reinforce existing conditioning and psychological limitation? An important question to ask, surely?

Culture by its very nature usually hides a collective mental programming built up over time, history and circumstance. Culture shapes thoughts, perceptions and behaviours without our explicit awareness. Our cultural lens subconsciously influences how we interpret events, behaviours and even our own emotional reactions. By extension in dialogue groups, are there shared yet concealed inner agendas, generating a whole dialogue culture and producing a kind of dialogue “tradition”? Just as we may be unaware of cultural habits influencing our attitudes and actions, similarly are we aware of this possible dialogue culture affecting us in our inquiry?

As a participant in dialogue, I probably have underlying desires about how I want the world, myself, or others to be. Do these unacknowledged wishes and intentions determine my level of enthusiasm or disappointment in the dialogue forum? When the outcome does not measure up to an anticipated fulfilment, is there then frustration or disturbance of some kind? In other words: is dialogue disappointing, or are we unaware of our own mind’s thwarted expectations?

During the exchanges and interactions, I might be irritated by a fellow participant in the group, yet completely ignorant of my hidden motivations severing the space between us. The irritation that is attributed to you, might in fact be inattention to the same, generating within me. Do I give attention to these reactions being set in motion, or do I not realise the impact of not giving attention? Lack of awareness in dialogue and the false assumptions that ensue, may be cultivating a whole cloud of conflict that I do not see that I am directly participating in.

On the other hand, one may react to this felt sense of disappointment and frustration by erecting an ideal version of dialogue in its place. Do I architect another kind of dialogue forum where spiritual ideals of love and positivity are cultivated for a more fulfilling even “sacred” experience? Does this version of dialogue propose itself as an enlightened guidance to a better, more advised life? Can the values of so called proper dialogue behaviour, intentional listening and righteous understanding, actually bring fundamental change to our deeply conditioned minds? Or, quite the contrary in this case, are we merely celebrating the glowing satisfaction of being turned into rather virtuous versions of ourselves!

We could say that we are like actors of a conditioned script written by the history of all humanity. Is it inevitable that our shared conditioning always program the very intention, content and function of our dialogue groups? And if so, can dialogue attempt to uncover this insidious programming? Alternatively, are we doomed to continually fall prey to it? Clearly, without realising the significance of these hidden psychological “scriptures” operating within us, dialogue and inquiry will unfortunately conceal a culture of perpetually unseen projections: a space where the very “atoms” of group relationship may divide and blow apart any potential unity or real inquiry.

In my view, the difficulty and the beauty of dialogue is in its direct mirroring of our shared collective human ignorance. Some will see the intrinsic value in looking into that which ordinarily seeks to remain hidden. Others will always seek beyond and ignore that which remains hidden.

Should dialogue be a “temple” where we celebrate the change we wish to be; or is dialogue a “template” that presents and illuminates the program of what we actually are?

If there were a more sustained interest in the process of dialogue: relaxing and listening directly to the assumptions enacting inside each one of us – we wouldn’t need dialogue to be a safe, entertaining or spiritually rewarding place. We would dare to discover the limitations we share, rather than disengage and be divided by the expectations we hold so dear.

We would not go to dialogue with a stubborn agenda that desires more for my already limited self: we would go and give absolutely everything we have, to partake in the uncovering of it all.

Per ardua ad astra

“Why are they in dialogue? Because they see the significance, they see the value of it. Therefore they form the purpose. It’s not to impose a purpose. If these people can see the significance and value, they will have the purpose and they will stick with it. Anybody who wants to do anything difficult has to go through difficulties and stick with it. Right?”

David Bohm – Interview on the dialogue process.

Jackie Mc Inley

Revised London December 2025